English below

Commentaires de l’ACRO sur le projet de rapport de la CIPR (les références sont à la fin du document, après la section en anglais) :

Un accident nucléaire ne peut pas être réduit à un problème de radioprotection car il a inévitablement des conséquences sociales, environnementales et économiques. La vie quotidienne des populations peut être profondément affectée. Ainsi, la CIPR propose une nouvelle publication sur les accidents graves qui concerne différents aspects de la réponse en prenant en compte tous les impacts. L’ACRO salue cette initiative mais regrette que le rapport soumis à la consultation du public ait des lacunes graves.

Niveaux de référence

Le principal problème concerne les niveaux de référence qui ne sont pas assez protecteurs. Tout d’abord, la CIPR considère « qu’il y a des preuves scientifiques fiables que l’exposition du corps entier à des niveaux supérieurs à 100 mSv peut augmenter la probabilité d’occurrence des cancers de la population exposée. En dessous de 100 mSv, la preuve est moins claire. Par prudence, la Commission suppose, pour toute la radioprotection, que même les faibles doses induisent une petite augmentation du risque » (22). Une telle affirmation ne prend pas en compte tous les résultats de la littérature scientifique. Dans les faits, ce projet de rapport reprend les niveaux de la publication 103 de la CIPR, qui sont les mêmes que ceux de la publication 60 qui remonte à 1990. Ces niveaux sont surtout basés sur le suivi des hibakusha de Hiroshima et Nagasaki (TD86). Il y a de nombreuses études en radiobiologie et en épidémiologie qui suggèrent fortement l’existence d’effets stochastiques en dessous de 100 mSv et que la relation linéaire sans seuil est basée sur des faits et pas seulement « sur une approche précautionneuse de la radioprotection ». Voir, par exemple, les réfs. [LD].

L’ACRO exhorte la CIPR à réduire les niveaux de référence et les limites qu’elle recommande.

Après un accident nucléaire, la CIPR recommande : « le niveau de référence pour la protection des intervenants après la phase d’urgence nucléaire ne doit pas dépasser 20 mSv par an. Pour les personnes qui vivent dans des zones durablement contaminées après la phase d’urgence, le niveau de référence doit être choisi dans ou sous l’intervalle de 1 à 20 mSv recommandé par la Commission pour ce qui est des situations d’exposition existantes, en prenant en compte la distribution des doses dans la population et la tolérance aux risques dans des situations d’exposition existantes durables. Et, d’une manière générale, il n’est pas nécessaire que le niveau de référence dépasse 10 mSv par an. L’objectif d’optimisation de la protection est une baisse progressive de l’exposition à des niveaux de l’ordre de 1 mSv par an » (j).

Comme cette position étant difficilement compréhensible, la CIPR ajoute : « La Commission considère que des expositions annuelles de l’ordre de 10 mSv durant les premières années du processus de réhabilitation, additionnées à l’exposition durant la phase d’urgence, pourraient conduire à une exposition totale plus grande que 100 mSv dans un temps relativement court pour les personnes affectées. Par conséquent, il n’est pas recommandé de sélectionner des niveaux de référence au-delà de 10 mSv par an quand il est estimé que de telles expositions peuvent durer plusieurs années, une fois que la phase de réhabilitation commence. De plus, l’expérience de Tchernobyl et de Fukushima a montré qu’avec des niveaux d’exposition de l’ordre de 10 mSv par an, il est difficile – étant données les multiples conséquences négatives, sociétales, économiques et environnementales associées à la présence durable d’une contamination radioactive et aux nombreuses restrictions imposées à la vie quotidienne par les actions de protection – de maintenir des conditions de vie, de travail et de production décentes et durables dans les zones affectées » (80).

L’introduction d’un nouveau niveau de référence à 10 mSv/an est bienvenu car le Japon, par exemple, maintient un niveau à 20 mSv/an depuis plus de 8 ans à Fukushima. La réduction progressive des niveaux d’exposition à des niveaux de l’ordre de 1 mSv/an, ou plus bas, n’est pas assez protectrice sans un échéancier. Par contraste, les directives des Etats-Unis requièrent le déplacement quand les personnes peuvent être exposées à 20 mSv ou plus durant la première année, et 5 mSv ou moins à partir de la seconde année. L’objectif à long terme est de maintenir les doses à ou en dessous de 50 mSv en 50 ans. Le guide des mesures de protection en cas de déplacement traite de l’exposition externe après le panache aux matières radioactives déposées et de l’inhalation de matières radioactives remises en suspension qui ont été initialement déposées au sol ou sur d’autres surfaces [USEPA1992, FEMA2013].

L’ACRO exhorte la CIPR à introduire d’autres niveaux de référence associés à un échéancier précis pour la dose cumulée au cours des années, comme aux Etats-Unis.

Il convient de garder à l’esprit que la population peut déjà avoir été exposée à des doses allant jusqu’à 100 mSv lors de la phase d’urgence.

En ce qui concerne la phase d’urgence, la CIPR déclare : « Pour l’optimisation des actions de protection durant la phase d’urgence, la Commission recommande que les niveaux de référence pour limiter l’exposition des populations affectées et des intervenants ne doit généralement pas dépasser 100 mSv. Cela peut être appliqué sur une période courte et, d’une manière générale ne doit pas dépasser un an » (77). Mais elle explique, plus loin, qu’« une situation d’exposition d’urgence peut être de très courte durée (heures ou jours), ou elle peut se prolonger sur une longue période (semaines, mois ou années) » (85). Une situation d’exposition d’urgence qui requiert des actions « urgentes » ne peut pas durer des mois, voire des années ! Ce n’est pas cohérent avec le niveau de référence de la CIPR pour les situations d’urgence qui ne doit pas dépasser un an. Si cette urgence dure plus d’un an, il n’y a plus de niveau de référence.

Par ailleurs, comme l’explique la CIPR, « pour les décisions prises lors de la phase d’urgence, dans l’éventualité d’un accident nucléaire, surtout dans les premier instants, le besoin d’agir rapidement ne permet pas l’implication des parties prenantes. » (51). Ainsi, l’extension de la situation d’urgence au-delà de durées raisonnables va entraver l’implication des parties prenantes.

Dans le cas de l’accident à la centrale de Fukushima dai-ichi, la CIPR rappelle que « le 22 avril 2011, les territoires situés au-delà de la zone de 20 km pour lesquels il a été estimé que la dose attendue en un an pouvait atteindre 20 mSv ont été désignés comme “zone d’évacuation intentionnelle”. Le gouvernement central a ordonné que la réinstallation des habitants des zones d’évacuation intentionnelle soit effectuée en à peu près un mois. Le critère d’évacuation choisi par le gouvernement a été établi en fonction de l’intervalle de niveaux de référence de 20 à 100 mSv par an pour les situations d’urgence recommandés par la CIPR » (B7). Un ordre d’évacuation issu 42 jours après la déclaration d’urgence avec plus d’un mois pour l’appliquer n’est PAS une évacuation d’urgence ! Les autorités japonaises ont trahi les citoyens en se référant aux situations d’exposition d’urgence.

En conclusion, la phase d’urgence doit être aussi courte que possible sinon les autorités vont se référer à des niveaux de référence les plus élevés et exclure l’implication des parties prenantes. Il est important de noter que, d’un point de vue purement physique, les radioéléments à vie courte dominent l’exposition externe durant un mois et qu’après les éléments à vie plus longue comme le césium radioactif dominent. Il n’est donc pas nécessaire d’étendre la phase d’urgence sur de longues durées.

L’ACRO exhorte la CIPR à réduire la phase d’urgence à la période la plus courte possible qui ne doit pas dépasser un mois.

Protection des enfants et des femmes enceintes

La CIPR « recommande de porter une attention particulière aux enfants et aux femmes enceintes, pour qui les risques radiologiques peuvent être élevés que pour les autres groupes d’individus. Les activités sociales et économiques stratégiques devraient également faire l’objet de dispositions de protection spécifiques dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre du processus d’optimisation. » (65) De fait, les fœtus et les jeunes enfants sont plus sensibles aux radiations que les adultes, mais la plupart des niveaux de référence et limites de doses ont été établis pour des adultes. Les recommandations de la CIPR visant à assurer une meilleure protection sont très décevantes. Elles incluent :

- « la surveillance de la dose à la thyroïde dans la phase initiale [qui] est importante pour les enfants et les femmes enceintes » (102);

- « l’administration d’iode stable durant la phase initiale [qui est particulièrement est importante pour les enfants et les femmes enceintes » (130);

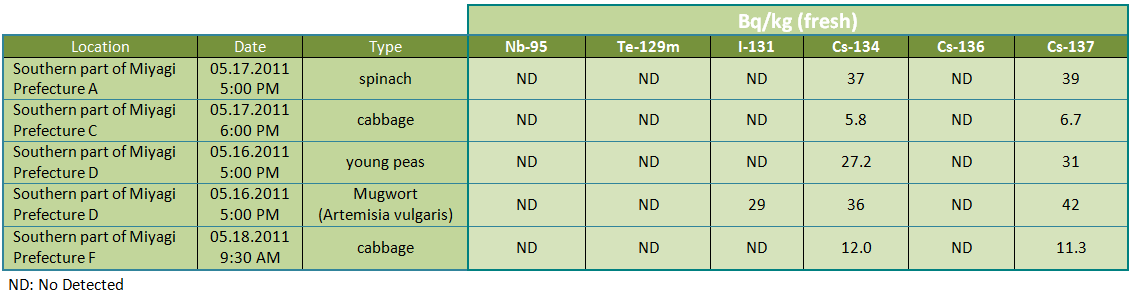

- « le contrôle de la qualité radiologique du lait, qui constitue une part importante de l’alimentation des enfants dans la plupart des pays, [et qui] est particulièrement important pendant la phase initiale d’un accident car il constitue une source potentielle d’exposition de la thyroïde à l’iode radioactif » (134);

- « Une sous-catégorie de la surveillance sanitaire [qui] est le suivi de sous-groupes potentiellement sensibles (par ex. les enfants, les femmes enceintes) » (198).

L’ACRO exhorte la CIPR à introduire des limites et des niveaux de référence plus protecteurs pour les femmes enceintes, les bébés et les enfants.

Evacuation et protection des populations

Étonnamment, le résumé analytique du projet de rapport ne mentionne pas les personnes déplacées et leur protection. Plus loin, dans le texte principal, la CIPR affirme que « l’expérience internationale après les accidents nucléaires et non nucléaires montre que les nations et les individus ne sont pas disposés à abandonner facilement les zones touchées » (57), ce qui n’est pas exact. A Fukushima, seulement 23% des personnes qui ont été obligées d’évacuer sont revenues après la levée des ordres d’évacuation. De plus, de nombreuses familles ont évacué seules, sans aucun soutien.

En outre, la CIPR ne prend en compte que la « réinstallation temporaire ». Dans les cas de Tchernobyl et de Fukushima, il existe encore de vastes zones où personne n’est autorisé à revenir et de nombreuses familles sont réinstallées ailleurs définitivement. Pourquoi la CIPR les ignore-t-elle ?

La CIPR semble considérer qu’une fois qu’elles ont quitté les zones contaminées, elles ne sont plus concernées par la radioprotection et ne méritent plus d’être prises en considération. Mais elles ont fui une exposition aux radiations !

Les personnes réinstallées ailleurs et les rapatriés devraient bénéficier de la même considération dans la publication. Les personnes déplacées souffrent de difficultés financières, de discrimination et de mise à l’écart (intimidation dans le cas des enfants). Beaucoup se sentent coupables d’avoir abandonné leur ville natale, ceux qui sont restés et ceux qui sont revenus. Ils ont besoin d’une protection et d’une attention particulières.

L’ébauche de la CIPR ne tient compte que des populations vivant dans des territoires contaminés qui n’ont pas été évacuées ou qui sont revenues. Il convient également de noter que de nombreux rapatriés ne vivent pas chez eux, mais ont été réinstallés dans un nouveau logement dans leur ville natale. Dans certaines villes et certains villages, ils doivent vivre dans un quartier complètement nouveau.

La CIPR note que « la réinstallation temporaire est cependant associée à des troubles psychologiques. Plusieurs études menées après l’accident de Fukushima ont montré une augmentation significative de l’incidence de la dépression et du syndrome de stress post-traumatique chez les résidents relogés de Fukushima » (136). Mais vivre dans des territoires contaminés est aussi associé à des troubles psychologiques et à un stress qui n’est jamais mentionné. Les travaux de terrain menés au Japon indiquent que ce traumatisme est réel [Shinrai2019 et ses références]. L’insistance sur les « troubles psychologiques dus à la réinstallation » cache le traumatisme de ceux qui sont restés, ou sont revenus, et se sentent “piégés” dans cette situation subie.

La seule solution proposée est la diffusion d’une culture radiologique pour apprendre à vivre dans des territoires contaminés avec une exposition aux radiations optimisée afin d’aider les gens à répondre à leurs préoccupations de la vie quotidienne. Cependant, la CIPR ne considère jamais que cela pourrait être un fardeau trop lourd pour beaucoup et que la plupart des familles aimeraient offrir un autre avenir à leurs enfants, sans avoir à vérifier et à évaluer constamment chaque mouvement de leur vie quotidienne.

La CIPR ne mentionne qu’une seule fois que « les individus ont le droit fondamental de décider s’ils veulent ou non rentrer chez eux. Toutes les décisions de rester dans une zone touchée ou de la quitter doivent être respectées et soutenues par les autorités, et des stratégies doivent être élaborées pour la réinstallation de ceux qui ne veulent pas ou ne sont pas autorisés à rentrer dans leur foyer » (158). Cela n’est pas suffisant et devrait être davantage étayé par des conseils pratiques aux autorités.

L’ACRO exhorte la CIPR à examiner sérieusement la question des populations déplacées et de se référer aux Principes directeurs relatifs au déplacement de personnes à l’intérieur de leur propre pays du Conseil économique et social des Nations Unies [UNESC1998]. Rappelant que « les déplacements engendrent presque toujours de graves souffrances pour les populations touchées », ces Principes directeurs relatifs au déplacement de personnes à l’intérieur de leur propre pays leur offrent des garanties. En particulier, « les autorités compétentes ont le devoir et la responsabilité première d’établir les conditions et de fournir les moyens qui permettent aux personnes déplacées à l’intérieur de leur propre pays de retourner volontairement, en toute sécurité et dignité, dans leurs foyers ou lieux de résidence habituelle, ou de se réinstaller volontairement dans une autre partie du pays. Ces autorités s’efforceront de faciliter la réintégration des personnes déplacées à l’intérieur de leur propre pays qui ont été rapatriées ou réinstallées. » Ils ajoutent que « les personnes déplacées à l’intérieur de leur propre pays ont le droit d’être protégées contre le retour forcé ou la réinstallation dans tout lieu où leur vie, leur sécurité, leur liberté et/ou leur santé seraient en danger » et que « des efforts particuliers devraient être faits pour assurer la pleine participation des personnes déplacées à la planification et à la gestion de leur retour ou de leur réinstallation et réintégration ».

Les personnes vulnérables sont particulièrement exposées en cas d’accident nucléaire grave. La CIPR reconnaît que « dans les mois qui ont suivi l’accident nucléaire de Fukushima, une augmentation générale de la mortalité a été observée (à l’exclusion des décès dus au séisme et au tsunami), notamment chez les personnes âgées. Cette augmentation ne peut être attribuée aux effets directs des rayonnements sur la santé, bien qu’elle soit une conséquence directe de l’accident » (40). En outre, « l’évacuation non planifiée de personnes âgées ou sous surveillance médicale de maisons de repos peut avoir causé plus de mal que de bien à ces personnes » (54). Ainsi, « l’évacuation peut être inappropriée pour certaines populations, comme les patients dans les hôpitaux et les maisons de repos, ainsi que les personnes âgées, si elle n’est pas bien planifiée » (124).

L’ACRO est d’accord avec la CIPR sur ce point, mais considère que l’hébergement prolongé des personnes vulnérables dans les zones exposées devrait être bien préparé. Le personnel doit accepter de prendre soin des patients malgré la situation radiologique.

Confiance et implication des parties prenantes

Dans son projet de rapport, la CIPR explique fréquemment qu’un accident nucléaire génère de la « complexité » ou des « situations complexes » sans expliquer le sens de ces expressions. Voir par exemple le § (15). Sans accident nucléaire, la vie et la société sont déjà complexes. Mais des individus et des groupes ont mis en place des mécanismes fondés sur la confiance pour faire face à une telle complexité. Un accident nucléaire remet en cause cette confiance et les populations touchées sont perdues devant une situation sans précédent. Ainsi, le principal défi pour les autorités est donc de fournir des informations dignes de confiance.

La CIPR mentionne une fois « l’effondrement de la confiance dans les experts et les autorités » (29) et suggère que « les actions de protection devraient contribuer à regagner la confiance de toutes les personnes par rapport à la zone affectée » (66). Mais la confiance doit être conservée plutôt que restaurée !

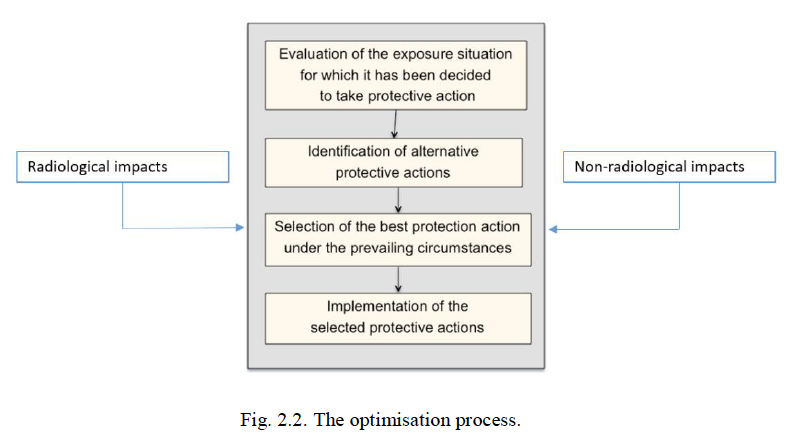

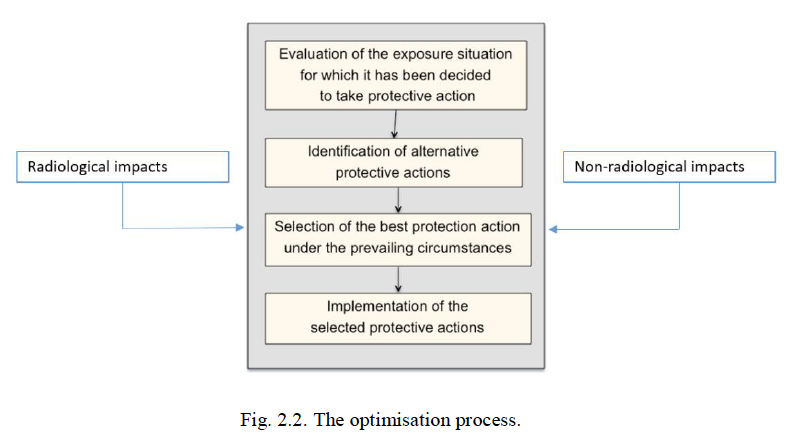

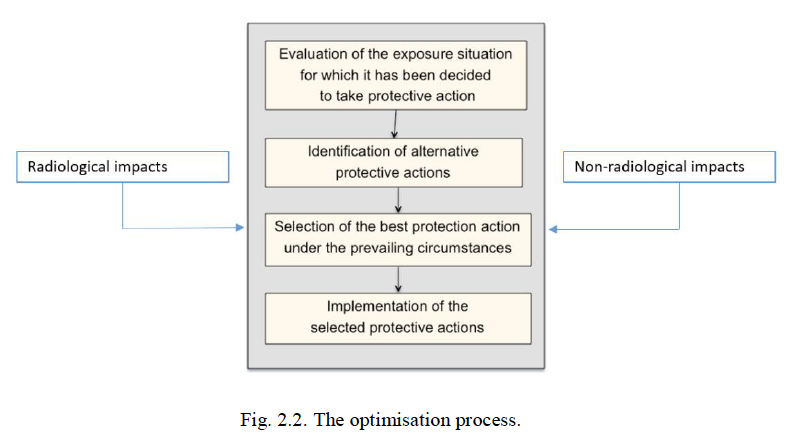

Les mesures de protection choisies doivent être expliquées et justifiées aux populations touchées. Ensuite, une réévaluation régulière est nécessaire en raison des grandes incertitudes qui sous-tendent le processus de décision précoce. Par conséquent, le processus étape par étape illustré à la figure 2.2 devrait être étendu pour inclure l’explication et la réévaluation. En outre, l’implication des parties prenantes doit être spécifiquement mentionnée ici.

La CIPR explique que « le processus d’optimisation doit reconnaître qu’il y a inévitablement des conflits d’intérêts et chercher à concilier les différences et les besoins des différents groupes. Par exemple, les producteurs de biens, de services et d’aliments souhaiteront poursuivre leur production, mais leur capacité à le faire est affectée par la volonté des consommateurs de recevoir et d’acheter ces articles » (66). Dans sa publication sur les fondements éthiques de la radioprotection, la CIPR a ignoré ces intérêts contradictoires et l’ACRO a considéré dans ses commentaires qu’il s’agissait d’une lacune majeure. Ainsi, l’ACRO est satisfaite de voir qu’ils sont reconnus ici. Cependant, la réponse est décevante : « Les mesures de protection devraient contribuer à regagner la confiance de toutes les personnes en ce qui concerne la zone touchée » (66). C’est tout !

Lorsque la CIPR recommande que « toute décision modifiant une situation d’exposition aux rayonnements devrait faire plus de bien que de mal » (48), tient-elle compte des individus, des groupes, de la nation ? Les intervenants seront exposés pour sauver les autres. La CIPR écrit plus loin : « La responsabilité de juger la justification incombe généralement aux autorités pour assurer un bénéfice global, au sens le plus large, à la société, et donc pas nécessairement à chaque individu » (50). Cette position est en conflit avec le droit à la santé de la Déclaration universelle des droits de l’homme : « Chaque individu personne a droit à un niveau de vie suffisant pour assurer sa santé, son bien-être et ceux de sa famille. »

Anand Grover, Rapporteur spécial du Conseil des droits de l’homme de l’ONU, a noté dans son rapport sur Fukushima : « Les recommandations de la CIPR sont basées sur les principes d’optimisation et de justification, selon lesquels toutes les actions du gouvernement devraient être basées sur la maximisation du bien par rapport au mal. Une telle analyse risques-avantages n’est pas conforme au cadre du droit à la santé, car elle donne la priorité aux intérêts collectifs sur les droits individuels. En vertu du droit à la santé, le droit de chaque individu doit être protégé. En outre, ces décisions, qui ont un impact à long terme sur la santé physique et mentale des personnes, devraient être prises avec leur participation active, directe et effective » [HRC2013].

L’ACRO exhorte la CIPR à se préoccuper sérieusement des conflits d’intérêts inhérents à ses principes de radioprotection avec la participation sincère parties prenantes.

A long terme, la CIPR encourage le processus de co-expertise et la participation des parties prenantes. L’ACRO soutient également une telle approche. Toutefois, les « dialogues de la CIPR » à Fukushima promus dans le projet de rapport ne sont pas un exemple à suivre, car ils se limitaient aux personnes partageant le point de vue de la CIPR et n’étaient mis en œuvre que dans quelques villes sélectionnées. Les opposants n’ont pas été autorisés à assister aux réunions. De telles réunions ne peuvent que générer des frustrations chez les personnes qui sont exclues ou qui se sentent exclues. Les dialogues devraient être ouverts à toutes les composantes des populations touchées.

Lors des réunions publiques, les participants sont confrontés aux autorités et à leurs experts pour traiter de questions complexes. Les gens ne sont donc pas en mesure de faire valoir leur point de vue, à moins qu’ils ne soient assistés par des experts qu’ils ont eux-mêmes choisis. Après un accident nucléaire grave, les gens sont encore plus vulnérables et ne peuvent pas tenir tête aux autorités. Les participants devraient également être en mesure de forger leur propre point de vue sans la présence des autorités avant d’engager le dialogue avec elles. De plus, le processus de co-expertise présenté dans le projet de rapport ne concerne qu’une minorité de la population qui est prête à lutter pour la récupération et la réhabilitation de la zone contaminée. Il ignore complètement les populations qui préféreraient d’autres solutions comme la réinstallation dans un autre lieu. Ils auraient aussi besoin d’un processus de co-expertise !

Enfin, en ce qui concerne la caractérisation de la situation radiologique, la CIPR écrit : « L’expérience montre que le pluralisme des organisations impliquées dans la mise en œuvre du système de surveillance radiologique (autorités, organismes experts, laboratoires locaux et nationaux, organisations non gouvernementales, instituts privés, universités, acteurs locaux, exploitants nucléaires, etc) est un facteur important en faveur de la confiance des populations envers les mesures » (161). L’ACRO est tout à fait d’accord sur ce point, mais il ne suffit pas d’accumuler des données et le suivi citoyen doit être soutenu financièrement. Les données devraient être facilement accessibles à tous et l’analyse indépendante devrait être soutenue. Les tendances et la modélisation sont également importantes pour un processus décisionnel.

L’ACRO demande à la CIPR à reconsidérer sa recommandation sur le processus de co-expertise et la participation des parties prenantes.

Protection des intervenants

En ce qui concerne les intervenants en situation d’urgence, la CIPR écrit : « Lorsqu’un travailleur professionnellement exposé intervient en tant qu’intervenant, l’exposition reçue pendant l’intervention doit être comptabilisée et enregistrée séparément des expositions reçues pendant les situations d’exposition prévues, et ne doit pas être prise en compte pour le respect des limites de dose professionnelle » (120). Cette recommandation est inacceptable.

Les doses reçues ont le même impact, qu’elles soient prises en situation d’urgence ou lors d’interventions planifiées, et elles se cumulent. A Fukushima, de nombreux intervenants résident en zone contaminée où ils continuent à être exposés, sans que cela soit pris en compte.

L’ACRO exhorte la CIPR à reconsidérer sa position : l’enregistrement des doses reçues par un intervenant doit prendre en compte toutes les situations d’exposition, de garantir le respect d’une valeur limite dose-vie qui ne devrait être pas excéder 500 mSv. La réglementation française retient une limite en dose-vie de 1000 mSv pour les intervenants en situation d’urgence radiologique. ACRO considère que cette dernière limite est trop élevée et qu’en outre elle devrait cumuler toutes les doses reçues en toute situation d’exposition.

Conclusions

Un accident nucléaire grave entraîne des dommages irréversibles mais ne peut être exclu. La CIPR devrait recommander que les efforts les plus importants soient déployés par les exploitants nucléaires pour éviter les accidents et que des autorités de sûreté nucléaire indépendantes imposent les normes les plus élevées. Si ces normes ne peuvent être respectées, la centrale nucléaire devrait être arrêtée.

ACRO’s comments on the ICRP draft report:

A nuclear accident cannot be reduced to a radiation protection problem as it has inevitably social, environmental and economic consequences. The daily life of people can be deeply affected. Thus, the ICRP has drafted a new publication on large accidents that takes into account various aspects of the response considering all impacts. ACRO welcomes this initiative but regrets that the draft submitted to public consultation has severe shortcomings.

Reference levels

The main problem is that reference levels are not protective enough. First of all, ICRP considers that “there is reliable scientific evidence that whole-body exposures on the order of ≥100 mSv can increase the probability of cancer occurring in an exposed population. Below 100 mSv, the evidence is less clear. The Commission prudently assumes, for purposes of radiological protection, that even small doses might result in a slight increase in risk” (22). Such statement does not take into account all the results of the scientific literature. As a matter of facts, this draft report reproduces the levels of the ICRP publication 103, which are the same as in ICRP publication 60 which dates back to 1990. These levels are mainly based on the follow-up of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki hibakushas (TD86). There are many other studies in radiobiology and in epidemiology that strongly suggest the existence of stochastic effects below 100 mSv and that the linear and non-threshold relationship is based on facts and not only “on a precautionary basis for the management of radiation protection.” See for example Refs. [LD].

ACRO urges ICRP to reduce the reference levels and limits it recommends.

After a nuclear disaster, ICRP recommends: “For protection of responders after the urgent emergency response, the reference level should not exceed 20 mSv per year. For people living in long-term contaminated areas following the emergency response, the reference level should be selected within or below the Commission’s recommended band of 1–20 mSv for existing exposure situations, taking into account the actual distribution of doses in the population and the tolerability of risk for the long-lasting existing exposure situations, and there is generally no need for the reference level to exceed 10 mSv per year. The objective of optimisation of protection is a progressive reduction in exposure to levels on the order of 1 mSv per year” (j).

As this statement is hardly understandable, ICRP adds: “The Commission considers that annual exposures of the order of 10 mSv during the first years of the recovery process, added to exposure received during the emergency response, could lead to total exposures greater than 100 mSv in a relatively short period of time for some affected people. Therefore, it is not recommended to select reference levels beyond 10 mSv per year when it is estimated that such exposures could continue for several years, which may be the case once the recovery phase starts. In addition, experience from Chernobyl and Fukushima has shown that for exposure levels of the order of 10 mSv per year, it is difficult – given the multiple societal, economic, and environmental negative consequences associated with the long-lasting presence of contamination, and the numerous restrictions imposed on everyday life by the protective actions – to maintain sustainable and decent living, working, and production conditions in affected areas” (80).

The introduction of a new reference level at 10 mSv/y is welcome since Japan, for example, sticks to 20 mSv/y more than 8 years on in Fukushima. The progressive reduction in exposure to levels on the order of 1 mSv/y or below is not protective enough without a time frame. In contrast, U.S. guidelines require relocation when people may be exposed to 20 mSv or more of radiation in the first year and 5 mSv or below from the second year. The long-term objectives are to keep doses at or below 50 mSv in 50 years. The relocation protective action guide addresses post-plume external exposure to deposited radioactive materials and inhalation of re-suspended radioactive materials that were initially deposited on the ground or other surfaces [USEPA1992, FEMA2013].

ACRO urges ICRP to introduce other reference levels accompanied by specific time frame for the cumulated doses over the years as in the USA.

It is worth reminding that the population may have already been exposed to doses up to 100 mSv during the emergency phase.

Regarding the emergency phase, the ICRP states: “For the optimisation of protective actions during the emergency response, the Commission recommends that the reference level for restricting exposures of the affected population and the emergency responders should generally not exceed 100 mSv. This may be applied for a short period, and should not generally exceed 1 year” (77). But it later explains that “an emergency exposure situation may be of very short duration (hours or days), or it may continue for an extended period of time (weeks, months, or years)” (85). An emergency that requires urgent actions cannot last months or even years! This is not consistent with ICRP’s reference level for emergency should not exceed one year. If the emergency lasts longer, there is no reference level anymore.

Moreover, as explained by ICRP, “for emergency response decisions, in the event of a nuclear accident, especially in the early phase, the need to act quickly is not conducive to stakeholder involvement” (51). Thus, extending emergency beyond reasonable periods of time will hinder stakeholder involvement.

In the case of the accident at the Fukushima dai-ichi nuclear power plant (NPP), the ICRP recalls that “on 22 April 2011, the area outside the 20-km zone for which it was estimated that the projected dose within 1 year of the accident could reach 20 mSv was designated as the ‘deliberate evacuation area’. The national government issued an order that relocation of people from the deliberate evacuation area should be implemented in approximately 1 month. The criterion for relocation was selected by the government with consideration of the 20–100-mSv per year band of reference levels for emergency exposure situations recommended by ICRP” (B7). An evacuation order released 42 days after the emergency declaration with more than a month to comply is NOT an emergency evacuation! Japanese authorities betrayed their citizen by referring to the emergency exposure situation.

As a conclusion, the emergency phase should be as short as possible otherwise authorities will refer to highest reference values and exclude stakeholder involvement. Note that on a purely physical point of view, short-lived radioelements generally dominate the external exposure for a month and then longer-lived nuclei such as radioactive caesium dominate. There is no need to extend the emergency phase to long duration.

ACRO urges ICRP to reduce the emergency phase to the shortest possible period of time that should not exceed a month.

Protection of children and pregnant women

ICRP “recommends paying particular attention to children and pregnant women, for whom radiological risks may be greater than for other groups of individuals. Strategic social and economic activities should also be the subject of specific protection provisions in implementation of the optimisation process.” (65) As a matter of facts, foetus and young children are more sensitive to radiations than adults but most of dose limits and reference levels were derived for adults. ICRP’s recommendations to enforce a better protection are very deceiving. They include:

- “thyroid dose monitoring in the early phase [that] is important for children and pregnant women.” (102)

- “administration of stable iodine during the early phase [that] is particularly important for pregnant women and children.” (130)

- “control of the radiological quality of milk, which is an important part of the diet of children in most countries, [that] is particularly important during the early phase of an accident because it is a potential source of thyroid exposure from radioactive iodine.” (134)

- “A subcategory of health monitoring [that] is the follow-up of potentially sensitive subgroups (e.g. children, pregnant women);” (198)

ACRO urges ICRP to introduce more protective limits and reference levels for pregnant women, infants and children.

Evacuation and protection of populations

Surprisingly, the executive summary of the draft report does not mention displaced people and their protection. Later, in the main text ICRP claims that “worldwide experience after nuclear and non-nuclear accidents shows that nations and individuals are not willing to readily abandon affected areas” (57), which is not correct. In Fukushima, only 23% of the people who were forced to evacuate have returned after the evacuation orders were lifted. In addition, many families evacuated on their own, without any support.

Moreover, ICRP only considers “temporally relocation”. In both Chernobyl and Fukushima cases, there are still vast zones where nobody is allowed to come back and many families are permanently relocated. Why are they ignored by the ICRP?

ICRP might consider that once they left the contaminated areas, they are not concerned by radiation protection anymore and they do not deserve to be considered. But they escaped radiation exposure!

Relocated people and returnees should benefit from the same consideration in the publication. Relocated people are suffering from financial difficulty, discrimination and marginalisation (bullying in case of children). Many feel guilty to have abandoned their hometown, those who remained and those who returned. They need special protection and consideration.

ICRP’s draft only considers populations living in contaminated territories who did not evacuate or who returned. Note also that many returnees do not live in their home but have been relocated in a new dwelling in their hometown. In some towns and villages, they have to live in a completely new district.

ICRP notes that “temporary relocation is, however, associated with psychological effects. Several studies carried out after the Fukushima accident showed significant increases in the incidence of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among relocated residents of Fukushima Prefecture” (136). But living in contaminated territories is also associated with psychological effects and stress that is never mentioned. Field work conducted in Japan indicates that this trauma is real [Shinrai2019 and references therein]. The insistence on the “psychological effects of relocation” hides the trauma of those who stayed, or returned, and feel “trapped” in this unchosen situation.

The only suggested solution is the dissemination of radiological culture to learn how to live in contaminated territories with an optimised radiation exposure to help people to address their daily life concerns. However, ICRP never considers that this could be a too heavy burden for many and that most families would like to offer another future to their children, free from a burden of constant checking and assessment of every move of their daily lives.

ICRP mentions only once that “individuals have a basic right to decide whether or not to return. All decisions about whether to remain in or leave an affected area should be respected and supported by the authorities, and strategies should be developed for resettlement of those who either do not want or are not permitted to move back to their homes” (158). This is not enough and should be more substantiated by practical advices to the authorities.

ACRO urges ICRP to seriously consider displaced populations and refer to the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement of the United Nations’ Economic and Social Council [UNESC1998]. Recalling that “displacement nearly always generates conditions of severe hardship and suffering for the affected populations”, these Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement provide them guaranties. In particular, “competent authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to establish conditions, as well as provide the means, which allow internally displaced persons to return voluntarily, in safety and with dignity, to their homes or places of habitual residence, or to resettle voluntarily in another part of the country. Such authorities shall endeavour to facilitate the reintegration of returned or resettled internally displaced persons.” They add that “internally displaced persons have the right to be protected against forcible return to or resettlement in any place where their life, safety, liberty and/or health would be at risk” and that “special efforts should be made to ensure the full participation of internally displaced persons in the planning and management of their return or resettlement and reintegration”.

Vulnerable people are particularly at risk in case of a severe nuclear accident. ICRP acknowledges that “during the months following the Fukushima nuclear accident, a general increase in mortality was observed (excluding deaths due to the earthquake and tsunami), especially among elderly people. This increase cannot be attributed to the direct health effects of radiation, although it is a direct consequence of the accident” (40). Also, “the unplanned evacuation of elderly or medically-supervised people from nursing homes may have caused more harm than good for these people” (54). Thus, “evacuation can be inappropriate for certain populations, such as patients in hospitals and nursing homes, as well as elderly people, if it is not well planned” (124).

ACRO agrees with ICRP on this point, but considers that extended sheltering of vulnerable people in exposed areas should be well prepared. Staff should agree to take care of patients in spite of the radiological situation.

Confidence and stakeholder’s involvement

In its draft report, ICRP frequently explains that a nuclear accident generates “complexity” or “complex situations” without explaining what does such expressions mean. See e.g. § (15). Without nuclear accident, life and society are already complex. But individuals and groups have built up mechanisms to face such complexity based on trust. A nuclear accident challenges this confidence and affected population are lost in front an unprecedented situation. Thus, the main challenge for authorities is to deliver trustworthy information.

ICRP mentions once “a collapse of trust in experts and authorities” (29) and suggests that “protective actions should contribute to regaining the confidence of all people in relation to the affected area” (66). But confidence should be kept rather than restored!

The selected protective actions should be explained and justified to the affected populations. Then, regular reassessment is necessary knowing the large uncertainties underlying the early decision process. Thus, the step-by-step process shown in Fig. 2.2 should be extended to include explanation and re-evaluation. Furthermore, stakeholder involvement should be specifically mentioned here.

ICRP explains that “the optimisation process must recognise that there are inevitable conflicting interests, and seek to reconcile the differences and needs of various groups. For example, producers of goods, services, and food will wish to continue production, but their ability to do so is affected by the willingness of consumers to receive and purchase these items” (66). In its publication on Ethical Foundations of Radiological Protection, ICRP ignored these conflicting interests and ACRO considered in its comments that it was a major shortcoming. Thus, ACRO is satisfied to see that they are acknowledged here. However, the response is disappointing: “protective actions should contribute to regaining the confidence of all people in relation to the affected area” (66). That’s all!

When ICRP recommends that “any decision altering a radiation exposure situation should do more good than harm” (48) does it consider individuals, groups, the nation? Responders will be exposed to save others. ICRP further writes: “Responsibility for judging justification usually falls on the authorities to ensure an overall benefit, in the broadest sense, to society, and thus not necessarily to each individual” (50). This position is in conflict with the right to health of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family”.

Anand Grover, Special Rapporteur to UN Human Rights Council, noted in his report on Fukushima: “ICRP recommendations are based on the principles of optimisation and justification, according to which all actions of the Government should be based on maximizing good over harm. Such a risk-benefit analysis is not in consonance with the right to health framework, as it gives precedence to collective interests over individual rights. Under the right to health, the right of every individual has to be protected. Moreover, such decisions, which have a long-term impact on the physical and mental health of people, should be taken with their active, direct and effective participation” [HRC2013].

ACRO urges ICRP to seriously address the conflicts of interest inherent to its radiation protection principles with a sincere involvement of stakeholder.

On the long term, ICRP promotes co-expertise process and stakeholder involvement. ACRO also supports such an approach. However, “ICRP dialogues” in Fukushima promoted in the draft report are not an example to follow as they were limited to people agreeing with ICRP’s point of view and only implemented in very few selected towns. Opponents were not allowed to attend the meetings. Such meetings can only generate frustrations to the people who are excluded or feel excluded. Dialogues should be open to all component of the affected populations.

At public meetings, participants are confronted with authorities and their experts to deal with complex issues. People are therefore not in a position to make their views considered, unless they are assisted by experts they have chosen themselves. After a severe nuclear accident, people are even more vulnerable and cannot stand up to the authorities. Participants should also be able to forge their own point of view without authorities before engaging dialogue with authorities. Moreover, the co-expertise process presented in the draft report is only for a minority of the population that is ready to fight for recovery and rehabilitation of the contaminated zone. It completely ignores populations who would prefer other solutions such as relocation. They would also need a co-expertise process!

Finally, regarding the characterisation of the radiological situation, ICRP writes: “Experience shows that the pluralism of organisations involved in implementation of the radiation monitoring system (authorities, expert bodies, local and national laboratories, non-governmental organisations, private institutes, universities, local stakeholders, nuclear operators, etc.) is an important factor in favour of confidence in the measurements among the affected population” (161). ACRO fully agrees with this, but accumulating data is not enough and citizen monitoring should be supported financially. Data should be easily accessible to anybody and independent analysis should be supported. Trends and modelling are also important for a decision process.

ACRO urges ICRP to reconsider its recommendation on the co-expertise process and stakeholder involvement.

Protection of the responders

Regarding the emergency responders, ICRP writes: “When an occupationally exposed worker is involved as a responder, the exposure received during the response should be accounted for and recorded separately from exposures received during planned exposure situations, and not taken into account for compliance with occupational dose limits” (120). This recommendation is not acceptable.

Exposure doses have the same impact, whether taken in an emergency situation or during planned interventions, and they are cumulative. In Fukushima, many workers are residing in contaminated areas where they continue to be exposed. These additional doses are not taken into account.

ACRO urges ICRP to reconsider its position: recording of doses received by responders must take into account all exposure situations, to ensure compliance with a dose-life limit value that should not exceed 500 mSv. French regulations set a life-dose limit of 1000 mSv for responders in a radiological emergency situation. ACRO considers that this latter limit is too high and that, in addition, it should include all doses received in any exposure situation.

Conclusions

A severe nuclear accident induces irreversible damages but cannot be ruled out. ICRP should recommend that upmost efforts are done by nuclear operators to avoid accidents and that independent nuclear safety authorities enforce the highest standard. If such standards cannot be fulfilled, the nuclear plant should be phased out.

References – Références

[FEMA2013] Federal Emergency Management Agency, Program Manual – Radiological Emergency Preparedness, June 2013

http://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1917-25045-9774/2013_rep_program_manual__final2_.pdf

[HRC2013] Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Anand Grover, Mission to Japan (15 – 26 November 2012), 2 May 2013 (A/HRC/23/41/Add.3)

http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session23/A-HRC-23-41-Add3_en.pdf

[LD] Some scientific publications related to the stochastic impact of low doses of radiation:

- Zhou H. et al. Radiation risk to low fluences of α particles may be greater than we thought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2001) 98(25): 14410–14415

- Rothkamm K. et al. Evidence for a lack of DNA double-strand break repair in human cells exposed to very low X-ray doses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2003) 100(9): 5057–5062

- Mancuso M. et al. Oncogenic bystander radiation effects in Patched heterozygous mouse cerebellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2008) 105(34): 12445–12450

- Löbrich M. et al. In vivo formation and repair of DNA double-strand breaks after computed tomography examinations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2005) 102(25): 8984–8989

- Beels L. et al. Dose-length product of scanners correlates with DNA damage in patients undergoing contrast CT. Eur. J. of Radiol. (2012) 81: 1495–1499

- Brenner DJ. Et al. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: Assessing what we really know. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2003) 100(24): 13761–137662

- Watanabe T. et al. Hiroshima survivors exposed to very low doses of A-bomb primary radiation showed a high risk for cancers. Environ. Health Prev. Med. (2008) 13(5): 264-70

- Ozaka K. et al. Studies of the Mortality of Atomic Bomb Survivors, Report 14, 1950–2003: An Overview of Cancer and Noncancer Diseases. Rad. Res. (2012) 177: 229-243

- Pearce M.S. et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet (2012) 380(9840):499-505.

- Mathews J.D. Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians. BMJ. (2013) 346:f2360

- Bollaerts K. et al. Childhood leukaemia near nuclear sites in Belgium, 2002–2008. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. (2018) 27(2): 184-191

- Hsieh WH. et al. 30 years follow-up and increased risks of breast cancer and leukaemia after long-term low-dose-rate radiation exposure. Br. J. Cancer (2017) 117(12): 1883-1887

- Spycher B.D. et al. Background Ionizing Radiation and the Risk of Childhood Cancer: A Census-Based Nationwide Cohort Study. Environ. Health Perpect. (2015) 123(6): 622-628

- Kendall G.M. et al. A record-based case–control study of natural background radiation and the incidence of childhood leukaemia and other cancers in Great Britain during 1980–2006. Leukemia (2013) 27(1):3-9.

- Richardson DB. et al. Risk of cancer from occupational exposure to ionising radiation: retrospective cohort study of workers in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States (INWORKS). BMJ (2015) 351: h5359.

- Little MP. et al. Leukaemia and myeloid malignancy among people exposed to low doses (<100 mSv) of ionising radiation during childhood: a pooled analysis of nine historical cohort studies. Lancet Haematol. (2018) 5(8): 346-e358.

- NCRP Commentary No. 27: Implications of recent epidemiologic studies for the linear-nonthreshold model and radiation protection. NCRP 2018.

[SHINRAI2019] Christine Fassert and Reiko Hasegawa, Shinrai research Project: The 3/11 accident and its social consequences – Case studies from Fukushima prefecture, Rapport IRSN/2019/00178

https://www.irsn.fr/FR/connaissances/Installations_nucleaires/Les-accidents-nucleaires/accident-fukushima-2011/fukushima-2019/Documents/IRSN-Report-2019-00178_Shinrai-Research-Project_032019.pdf

[UNESC1998] United Nations, Economic and Social Council, Commission on Human Rights 1998, Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2, 11th February 1998

http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/IDPersons/Pages/Standards.aspx

[USEPA1992] United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Radiation Programs, Manual of Protective Action Guides and Protective Actions for Nuclear Incidents, Revised 1991, second printing, May 1992. EPA-400-R-92-001.

http://www.epa.gov/radiation/docs/er/400-r-92-001.pdf

©Olga Kaskevich

©Olga Kaskevich